By Peter Thorn

What follows is an edited transcript of a tour of St Mary’s conducted by Peter Thorn. Please read on to learn more about our beautiful church.

Princess Marie-Louise of Schleswig-Holstein (1872-1956) enjoyed a significant association with St Mary’s. When she attended the consecration in 1936, she saw over the door the crowned letters M & L, with a princess’s coronet, and concluded that Father Johnson was paying her a marvellous compliment. In fact, of course, M & L refer to St Mary and St Leonard, but such was the Princess’s pleasure that she gave the Vicar a handsome cheque.

Princess Marie-Louise of Schleswig-Holstein (1872-1956) enjoyed a significant association with St Mary’s. When she attended the consecration in 1936, she saw over the door the crowned letters M & L, with a princess’s coronet, and concluded that Father Johnson was paying her a marvellous compliment. In fact, of course, M & L refer to St Mary and St Leonard, but such was the Princess’s pleasure that she gave the Vicar a handsome cheque.

Over the door there is a large statue of the Virgin and Child. It was carved by Herbert Palliser. More of his work can be found inside the church. He was Professor of Sculpture at the Royal Academy and he was the tutor of Jacob Epstein. There was supposed to have been a dedicatory inscription underneath the statue but this was never erected.

The architect of the church was Harold Gibbons, the last architect working in church art who built in the mediaeval style. Most other churches built around here in the twenties and thirties – such as St Alban, North Harrow; All Saints, Queensbury; St Michael,Harrow Weald, and other neighbouring parishes – are all very modern buildings, contemporary to the 1920’s and 30’s, but in Kenton, a deliberate attempt was made to give an air of antiquity to the parish, because there were no other old buildings in Kenton. This church is unique in lending this more old-world appearance to church life locally, and that shows the continuity of the church of the past with the present and the future.

Just past the west door, engraved in the stone, are the Greek letters Chi and Rho (a symbol of Christ), which the Bishop traced when the church was consecrated.

Just past the west door, engraved in the stone, are the Greek letters Chi and Rho (a symbol of Christ), which the Bishop traced when the church was consecrated.

The cost of building the structure was £17,790. The fittings inside came to the princely sum of £2,950, and the church could accommodate 600 people, including a choir.

The building is of brick with stone dressing and rendering. It is all rendered inside. It has a timber roof and the roof is one of the glories of the church. It is covered with handmade tiles. There was a low pressure hot water system but that has long gone. The inside of the church is very much as it was in 1936.

Stones from a number of English shrines and abbeys, all of which were dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary, are embedded in the walls. There are also some leaves from the Virgin’s Tree in Egypt, under which the Holy Family are supposed to have slept on their way to Egypt.

Stones from a number of English shrines and abbeys, all of which were dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary, are embedded in the walls. There are also some leaves from the Virgin’s Tree in Egypt, under which the Holy Family are supposed to have slept on their way to Egypt.

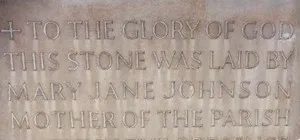

The Foundation Stone shows the name of the architect and the builder, Melsom and Rosier, who were a firm of builders in Wealdstone. This church was built by local people. Also in this corner is the stone laid by Fr Johnson’s mother, and the foundation stone of the church in Charing Cross Road (which was sold and the money given to build this church). There is also a stone from All Saints Church in York, where the first Vicar worshipped as a boy, and that stone dates from the year 1089.

The Calvary has an interesting history. The large bronze crucifix was sculptured by a man called Arthur Toft, also known as Tofts. He made a lot of war memorials after the First War.

The Calvary has an interesting history. The large bronze crucifix was sculptured by a man called Arthur Toft, also known as Tofts. He made a lot of war memorials after the First War.

It was made for a church in the City of London; however, a dispute meant that it was never installed in its original church. When this church was built, the Bishop of London gave it to Kenton.

This is regarded as the memorial corner, as there is a window to the British Legion, a war memorial and a chantry book of the names of all the departed who are remembered every day in the prayers of the church.

Fonts were always by tradition at the door of the church, because one went to church as a baby new-born into the world and were then born again into the Church through Baptism.

Fonts were always by tradition at the door of the church, because one went to church as a baby new-born into the world and were then born again into the Church through Baptism.

This font was the gift of Mr Nash of Nash Builders. It was carved in one piece of Minchinhampton stone by the sculptor, Herbert Palliser. At the front there a panel depicts Christ’s baptism by John the Baptist, symbolising the link between our baptism and His.

The font cover has an inscription round it taken from St John’s Gospel: ‘I am come that they may have life and that they may have it abundantly’, a message which exemplifies the spirit of St Mary’s – a community called to a life of worship, but in the context of the wholeness of life, within and beyond the physical church building.

The font has around it all sorts of symbols of childhood, including a dove, and round the crown of the canopy all sorts of elves and pixies etc. There are rabbits, lambs, dogs and cats.

The stained glass windows are very ancient. They are Georgian windows from about 1760. They are some of the oldest things in the church and they are known as York glass. They were made in York and they depict Eli and Samuel; the sacrifice of Isaac by Abraham, and the figures of Our Lord as a child from the New Testament. Unfortunately, one was broken some years ago by boys :conkering: in the Vicarage garden. The windows were given in memory of a little girl, the daughter of one of the early members of the congregation, who died. On the wall there is a very lovely bronze statue of the infant Christ.

Situated on the south wall, between the eleventh and twelfth Stations of the Cross, is an Icon which was presented to St Mary’s on 14 January 1996 by the Greek Orthodox Community in Kenton. The Icon depicts their Patron Saint, Panteleimon, a martyr of the early Church. This icon stands as a symbol and a constant reminder of the friendship and fellowship existing between our two ecclesiastical communities.

Situated on the south wall, between the eleventh and twelfth Stations of the Cross, is an Icon which was presented to St Mary’s on 14 January 1996 by the Greek Orthodox Community in Kenton. The Icon depicts their Patron Saint, Panteleimon, a martyr of the early Church. This icon stands as a symbol and a constant reminder of the friendship and fellowship existing between our two ecclesiastical communities.

According to the martyrologies, Panteleimon was the son of a rich pagan, Eustorgius of Nicomedia, and had been instructed in Christianity by his Christian mother, Saint Eubula; however, after her death he fell away from the Christian Church, while he studied medicine with a renowned physician, Euphrosinos; under the patronage of Euphrosinos he became physician to the Emperor Maximian or Galerius.

He was won back to Christianity by Saint Hermolaus (characterized as a bishop of the church at Nicomedia in the later literature), who convinced him that Christ was the better physician.

By miraculously healing a blind man by invoking the name of Jesus over him, Panteleimon converted his father, upon whose death he came into possession of a large fortune; with this the saint freed his slaves and, distributing his wealth among the poor, developed a great reputation in Nicomedia. Envious colleagues denounced him to the emperor during the Diocletian persecution. The emperor wished to save him and sought to persuade him to apostasise. Panteleimon, however, openly confessed his faith, and as proof that Christ is the true God, healed a paralytic. Notwithstanding this, he was condemned to death by the emperor, who regarded the miracle as an exhibition of magic.

When this church was built there was a desire not to interrupt the choir with the introduction of a choir. The choir is thus in the gallery above the west door.

When this church was built there was a desire not to interrupt the choir with the introduction of a choir. The choir is thus in the gallery above the west door.

This church was not built for simple, quiet services. It was built for full-blooded ceremonial worship on a grand scale, which has more or less continued in various forms ever since. Everything that happens at the great ceremonies of the liturgy can be seen fully by the people in the congregation. Equally, the pulpit is very prominent. One cannot mistake the pulpit here, any more than one can the font.

The ceiling goes the whole length of the church – and those who have had the privilege to go into the roof will testify it is the most wonderful, wooden construction, quite the equal of anything built in the mediaeval period. There is a marvellous wooden vault above the ceiling, which is one of the glories of the church. One can walk the whole length, right up to above the altar, and there are windows at both ends to let in the light. There is quite a big gap between there and the pointed roof outside.

Around the walls of the church there are the Stations of the Cross, which represent fourteen incidents in Our Lord’s journey from his judgement by Pilate to his burial after the crucifixion. Each panel is molded in bas relief in a composite material, like the font, and they were designed by Herbert Palliser, the sculptor, and carved by his students. Several students were given a different one to carve.

This organ incorporates the pipework and manual soundboards of an old and smaller Walker organ that formally stood in the church of St Mary-the-Virgin, Charing Cross Road. Otherwise the instrument is entirely new and the tonal scheme has been enlarged and completely remodelled by the use of several new unit chests and much new pipework, including new Open Diapason tasses; Dulciana 16-ft, 73 pipes; Twelfth; Tromba; Clarinet; Viola da Gamba bass; Mixture; Contra Fagotto; Trumpet; Open Diapason 16-ft.; Trombone, etc. Extension ranks are employed for the Great and Pedal Dulcianas, and the Swell Contra Fagotto and Oboe. The Pedal Open Diapason, metal, is an extension of the Great Open Diapason No. 1, and the Trombone is extended from the Tromba. All pipework is on a wind pressure of 5 inches.

This organ incorporates the pipework and manual soundboards of an old and smaller Walker organ that formally stood in the church of St Mary-the-Virgin, Charing Cross Road. Otherwise the instrument is entirely new and the tonal scheme has been enlarged and completely remodelled by the use of several new unit chests and much new pipework, including new Open Diapason tasses; Dulciana 16-ft, 73 pipes; Twelfth; Tromba; Clarinet; Viola da Gamba bass; Mixture; Contra Fagotto; Trumpet; Open Diapason 16-ft.; Trombone, etc. Extension ranks are employed for the Great and Pedal Dulcianas, and the Swell Contra Fagotto and Oboe. The Pedal Open Diapason, metal, is an extension of the Great Open Diapason No. 1, and the Trombone is extended from the Tromba. All pipework is on a wind pressure of 5 inches.

The organ represents a large and resourceful two-manual instrument built into a compact and divided position on the west end gallery, with console detached and placed centrally in front. The choir is also seated on the gallery. The organ was put into use on Sunday, 21 March 1937, and the casework installed in January 1938.

Renovations to the organ began after Easter in 1989, including adding a stop designed to give added brilliance to the tone. This was afforded after an organ fund was set up and a generous legacy was received from Rene Balaam.

There is something rather interesting on the side of the pulpit. Fr Johnson, the first Vicar, liked to believe that there had been a mediæval chapel in Kenton. There was a piece of land in the area called Priestmead and, in the Middle Ages, the money from that land went to support a priest who worked in the chapel of St Mary at Harrow-on-the-Hill – a sort of chantry chapel.

There is something rather interesting on the side of the pulpit. Fr Johnson, the first Vicar, liked to believe that there had been a mediæval chapel in Kenton. There was a piece of land in the area called Priestmead and, in the Middle Ages, the money from that land went to support a priest who worked in the chapel of St Mary at Harrow-on-the-Hill – a sort of chantry chapel.

That did not deter Fr Johnson from believing there had been a chapel here, and he dreamed up the idea that St Anselm, Archbishop of Canterbury, had consecrated it.

Archbishops of Canterbury used to live at Harrow-on-the-Hill, which was their main residence until the time of Henry VIII. So, when Fr Johnson built this church, he had carved into the pulpit the image of St Anselm coming to consecrate St Mary’s. However this is admittedly rather fanciful.

Outside we saw the M L for Princess Marie-Louise; the first sermon preached here was by Bishop Winnington-Ingram and, as he mounted the pulpit, he must have had a great surprise, because the figure carved of St Anselm actually had Bishop Winnington-Ingram’s features, so the Bishop looked at himself as he went to the pulpit.

At the centre of the crossing there is a carved roof boss. It is a copy of the roof boss under the choir screen in York Minster and it shows the Assumption of the Virgin Mary, to whom this church is dedicated. Fr Johnson had that carved as a reminder of York so that when he looked up from his stall he could see something he had looked at every day as a boy in York. Above the Sanctuary is the Rood Beam.

At the centre of the crossing there is a carved roof boss. It is a copy of the roof boss under the choir screen in York Minster and it shows the Assumption of the Virgin Mary, to whom this church is dedicated. Fr Johnson had that carved as a reminder of York so that when he looked up from his stall he could see something he had looked at every day as a boy in York. Above the Sanctuary is the Rood Beam.

Rood is the Anglo-Saxon word for cross. It depicts Our Lord with Our Lady and St John. Beneath them can be seen Our Lady’s coat of arms, the heart pierced with a sword following the prophecy of Simeon in St Luke’s Gospel, and under St John there is an eagle. At the two corners are shields bearing the symbols of the Passion of Christ, the crown of thorns, the nails, the cross, the pincers, the hammer, the spear and the lance.

Beneath the figure of Christ on the cross there is a skull. Golgotha means the place of the skull. In the Middle Ages it was believed that the skull on Golgotha was in fact the skull of Adam, so that as the first man died, so a new Adam also died and brought about redemption. To mediæval man that would have symbolised the two covenants.

The first Vicar came from York and as a boy he had vowed that if he became a priest he would build a church and dedicate it to St Leonard. St Leonard was a sixth-century French monk about whom almost nothing is known. He was buried at Naublac in France. St Leonard was very popular in the Middle Ages in England because he was the patron saint of prisoners. In the Middles Ages, particularly at the time of the Crusades, when the Crusaders were imprisoned by the Saracens, money was raised under the patronage of St Leonard to ransom the captives, and many churches were dedicated in his honour, including in York the hospital, the remains of which are by the Leadenhall Bridge. When Henry VIII decided to meddle in the affairs of the Church of England, the first religious house he closed in this country was St Leonard’s Hospital in York. It was run by a group of people called bedesmen who provided a refuge and home for the sick and dying, rather like a hospice would today. Fr Johnson, as a boy, made a vow that, as an act of reparation for the destruction of the hospital in York, when he built a church he would dedicate it to St Leonard. That is why the first church was called St Leonard’s, and why St Mary’s is in St Leonard’s Avenue. This chapel is dedicated to St Leonard to perpetuate that old memory.

The first Vicar came from York and as a boy he had vowed that if he became a priest he would build a church and dedicate it to St Leonard. St Leonard was a sixth-century French monk about whom almost nothing is known. He was buried at Naublac in France. St Leonard was very popular in the Middle Ages in England because he was the patron saint of prisoners. In the Middles Ages, particularly at the time of the Crusades, when the Crusaders were imprisoned by the Saracens, money was raised under the patronage of St Leonard to ransom the captives, and many churches were dedicated in his honour, including in York the hospital, the remains of which are by the Leadenhall Bridge. When Henry VIII decided to meddle in the affairs of the Church of England, the first religious house he closed in this country was St Leonard’s Hospital in York. It was run by a group of people called bedesmen who provided a refuge and home for the sick and dying, rather like a hospice would today. Fr Johnson, as a boy, made a vow that, as an act of reparation for the destruction of the hospital in York, when he built a church he would dedicate it to St Leonard. That is why the first church was called St Leonard’s, and why St Mary’s is in St Leonard’s Avenue. This chapel is dedicated to St Leonard to perpetuate that old memory.

On the wall there is an image of St Leonard in his monk’s robe, carrying the chains of captives and prisoners. Below the canopy is a hog, which is one of the symbols of St Leonard, and lilies of the valley which in the Middle Ages were known as St Leonard’s lilies. He presides over his chapel in St Mary’s carrying his pastoral staff which, because he was an abbot, is facing inwards. A bishop carries it facing outwards. The picture in the stained glass window again depicts St Leonard feeding the prisoners, with symbols of Our Lady above and St Leonard’s chains below. This altar is made of alabaster and there was supposed to be an alabaster screen but the money ran out. When this church was built it was hoped that all the weekday services would be held here in honour of St Leonard.

When this church was built, a lot of effort was made to copy ancient symbolism, and in the sanctuary there is indeed much symbolism drawn from the Bible. In the Book of Revelation it tells us that the golden altar in Heaven had before it a sea of glass. The altar in the Sanctuary is golden marble and on the floor is the sea of glass – sea-green marble.

When this church was built, a lot of effort was made to copy ancient symbolism, and in the sanctuary there is indeed much symbolism drawn from the Bible. In the Book of Revelation it tells us that the golden altar in Heaven had before it a sea of glass. The altar in the Sanctuary is golden marble and on the floor is the sea of glass – sea-green marble.

The most striking feature in the Sanctuary is the canopy over the altar. The canopy’s technical name is a “baldacchino”, which is an Italian word for Baghdad. These canopies over altars in Italy had round them curtains made out of silk imported from Baghdad and eventually this word “baldacchino” was applied to the whole covering.

Altars, when originally built, were built over the tombs of the martyrs – and altars should, even today, contain relics of the saints. In the high altar at St Mary’s you will find relics of St Victorinus and St Valentine. The very small portion of their bones are incorporated in the centre of the altar and sealed by the Bishop when he consecrated the altar. There is a letter from Bishop O’Rourke in 1932. In it he writes that a reliquary of ebony and silver had been sent to Fr Johnson containing relics of the martyrs Victorinus and Valentine.

The history of St Mary’s as a parish goes back quite a long way, into the last century, when Kenton was a very small hamlet and a lay reader from St Mary, Harrow-on-the-Hill came down to Kenton on Sunday evenings to say Evensong at Kenton School near where Gooseacre Lane is now.

That lay reader was a Mr William Moss and he happened to be at Harrow School. One of his pupils was a nephew of the Tsar of Russia and when the Russian prince went back to Russia, the Tsar sent a gift to Mr Moss, the icon on the pillar to the left of the altar. There is a letter which states: ‘The Imperial Russian Embassy in London is directed and has the honour herewith to forward to Mr W Moss a sacred picture of Our Saviour which His Majesty, the Emperor, has been graciously pleased to desire that it may be presented to him.’ It is signed by the First Secretary to the Russian Embassy. Mr Moss had a lot to do when this church was built and when he died, a Gothic cape with his name on was put round the icon which has the hallmarks of Moscow 1906. That was the gift of the last Tsar of Russia to St Mary’s, a very great treasure of historic importance.

There is another piece of flattery in the church. Above the canopy, over the altar, is the image of Christ the King that was carved with the features of King George V. The baldacchino at St Mary’s, as with a great deal of religous artefacts, has a deliberate mistake made on the edge of the floral decoration to show that only God can achieve perfection.

The canopy above the statue of Our Lady of Peace came from a church in Belgium which was destroyed in the First World War. It was collected by a Major Merchant who was one of the founding members of the congregation. When the church was built he had it placed over the statue of Our Lady of Peace.

The statue was sculptured by Mr Palliser. Money was collected to have it cast in bronze and everybody believed it was, until Fr Jermyn, the third Vicar, moved it and it proved to be made of plaster.

Mr Palliser’s daughter turned up one day and asked to see her father’s bronze statue. She was told that she could, but it wasn’t bronze. She was most displeased about that. It is not known what happened to the bronze one or whether it was even ever cast.

The windows above the South Aisle are copies of the mediæval windows in All Saints, North Street, York. They were given to Fr Johnson by the congregation of the church where he had been as a boy in York. They depict the Virgin and her mother, St Anne above, and below is the Archbishop, St William of York, having a vision of God the Father whilst saying Mass.

This is where the Blessed Sacrament is reserved perpetually in church for the priest to take to the sick or dying at any time of the day or night. The consecrated bread is kept in the tabernacle – a fairly new item but one which incorporates the door of the old one. There is another tabernacle (or aumbry) in the wall which contains the holy oils with which the priest anoints the sick or dying and also those being baptised. The roof boss is a pelican. The pelican also appears on the top of the canopy over the altar. In the Middle Ages, the pelican was believed to feed its young by plucking its breast for the blood would flow and the chicks to feed off. To mediæval man this was a symbol of Christ who feeds us in the Eucharist with his blood. The other bosses are from the church in Charing Cross Road mentioned earlier. Two are angels with portable organs and there is an angel with the chalice of the Eucharist and the Bible with the scriptures. Together these symbols combine as a witness to the Sacrament which is celebrated here.

This is where the Blessed Sacrament is reserved perpetually in church for the priest to take to the sick or dying at any time of the day or night. The consecrated bread is kept in the tabernacle – a fairly new item but one which incorporates the door of the old one. There is another tabernacle (or aumbry) in the wall which contains the holy oils with which the priest anoints the sick or dying and also those being baptised. The roof boss is a pelican. The pelican also appears on the top of the canopy over the altar. In the Middle Ages, the pelican was believed to feed its young by plucking its breast for the blood would flow and the chicks to feed off. To mediæval man this was a symbol of Christ who feeds us in the Eucharist with his blood. The other bosses are from the church in Charing Cross Road mentioned earlier. Two are angels with portable organs and there is an angel with the chalice of the Eucharist and the Bible with the scriptures. Together these symbols combine as a witness to the Sacrament which is celebrated here.

The picture above the altar has been there since 1976. Fr Jermyn, the third Vicar, had been Vicar of a parish in Norfolk and in the manor house at Gunthorpe where Captain Sparks lived there was this marvellous 19th century picture, a copy of the Virgin and Child by Murillo. This picture was ultimately given to the parish. The stained glass window in the south wall shows Mrs Johnson at prayer amid the green fields of Kenton. St Mary’s appears in the background as it was planned, with various pinnacles and bits that were never built – an interesting historical record.

Mention was made earlier of the gift from the Tsar of Russia. Queen Mary and the present Queen Mother gave some gifts to this church. In the 1920’s the Diocese of London had a fund called the Forty Churches Fund which was to build forty churches in the London suburbs. A meeting was held at St James’ Palace in 1928. The then Duchess of York, the late Queen Mother, went to this meeting and Fr Johnson gave a talk. After the meeting, she spoke with the Queen and they decided to send gifts to St Mary’s.

The Queen gave an Icon (also in the south wall) which was given to her father, the Duke of Teck, when he went on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land in the 1880’s with the Kaiser and King Edward VII, then Prince of Wales. The Patriarch of Jerusalem gave this to the Duke. It is over 300 years old and shows St Nicholas, the Virgin Mary, Christ harrowing hell, the three Marys at the tomb, St George, St Theodore and the saints of Mount Sinai.

Their faces are painted and there is a silver cover known as a “riza” placed over the paintings. A riza is designed specifically for the icon it is to cover. It leaves open spaces where the face, hands, and feet of the icon’s subject can be seen, although in this case only the faces. The haloes on rizas are often more elaborate than on the original icons. The purpose of a riza is to honour and venerate an icon, and ultimately the figure depicted on it. Because candles and lampadas (oil lamps) are burned in front of icons, and incense is used during services, icons can become darkened over time. The riza helps protect the icon.

The Icon was not the only thing Queen Mary gave St Mary’s. In 1911 she had a Durbar with her husband, George V, in Delhi when she was crowned Empress of India and she sent to St Mary’s the Durbar dress.

It was made into an altar frontal and a set of vestments which despite their fragility are still used at Easter and Christmas. Queen Mary also gave a very fine Spanish silver Corpus which is on the High Altar cross.